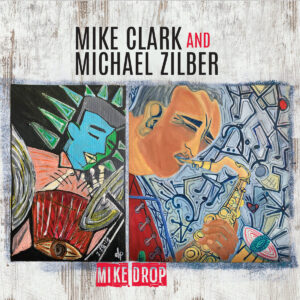

Words are fully inadequate to express my immense gratitude to Wayne Shorter as a composer and sax player, though I will give it a try later after more reflection. But for now, here is a song I wrote for him after his passing, being performed for the first time at Small’s in Manhattan on March 16 with the Mike Clark-Mike Zilber quartet.